Focusing on “Left of Boom”

The security community was recently transfixed by rapidly evolving events in Ukraine in mid-January 2022: First, a large-scale web defacement campaign, then revelations of concurrent (if not necessarily closely coordinated) wiper activity, given the name “WhisperGate,” against targets in the region. Once news of the latter emerged, security researchers rushed to analyze the malware in question (of which only one sample of each “stage” is known as of this writing) and publish their findings.

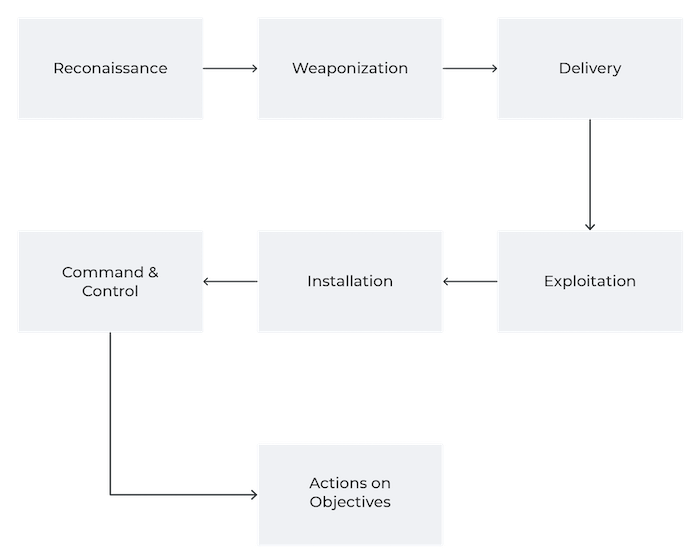

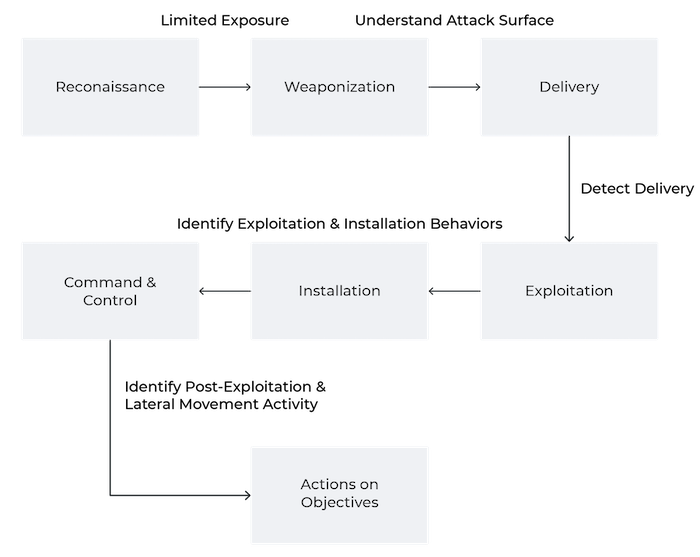

While these events are concerning due to overall geopolitical context and potential event significance, the overwhelming focus of information security resources on the execution of destructive malware in victim environments is misplaced. If we map what is known about the events in Ukraine to the Cyber Kill Chain, the WhisperGate wiper malware (and related tools) represent the final stages of adversary activity in victim environments.

If we were to compare WhisperGate’s execution to a bomb going off, detection of WhisperGate itself represents awareness and defense at the time of explosion: The adversary has succeeded in placing, setting, and arming the bomb, and it has exploded. From a defensive standpoint, our preference would be to detect and disrupt operations as far “left of boom” as possible to avoid worst-case outcomes.

Focusing resources and research on the final phase of adversary activity, whether a likely state-sponsored destructive item like WhisperGate or more general ransomware execution, ignores all preceding steps through which adversaries must be successful in order to execute actions on desired objectives — essentially, ceding initiative and time to threat actors that defenders could otherwise use to detect and mitigate intrusions at earlier stages. As shown in the following diagram, adversaries must migrate through various operational phases, each dependent on succeeding in prior steps, to achieve their objectives. Defenders can leverage these inherent attacker dependencies to build and deploy in-depth defense for monitored networks.

Looking specifically at the WhisperGate incidents and (potentially) related activity, information is unfortunately limited concerning early-phase intrusion activities. However, such information is not completely absent, as reports from several entities, including the Ukrainian CERT, provide enough context to identify general behaviors and techniques used by the adversary:

- Use of compromised credentials to access victim environments via single-factor authentication

- File staging in standard, default directories such as “C:\ProgramData” and “C:\temp”

- Remote execution using tools associated with the Impacket collection of scripts

- Use of Discord as a content delivery network (CDN) to stage and then retrieve follow-on tools as part of the destructive process

The above items are hardly unique for intrusions, whether discussing state-directed threats or ransomware operators. Yet they also represent the most likely areas defenders can vector resources to gain visibility or improve immediate defensive outcomes. By understanding these higher-level behaviors and the means through which they can be detected — in host or in network visibility — defenders can meaningfully learn from the campaign ending in WhisperGate in such a fashion as to identify similar intrusions at earlier, more actionable phases of the adversary’s lifecycle.

One challenge in a behavior-focused approach to security is the difficulty in translating an understanding of behaviors into technical observables or signatures. Such concerns can be reduced to a simple complaint that none of the noted behaviors are reducible to a single, semi-actionable “indicator of compromise” (IOC), such as the malware hashes for WhisperGate. Yet given the debasement of IOCs for defensive purposes, the utility of a couple of malware hashes is highly debatable. The underlying source code for WhisperGate can be compiled, packed, obfuscated, or otherwise presented in myriad ways (including purely in memory, as seen in later stages of WhisperGate actions) that will produce a nearly unlimited number of hashes for defenders to track.

Instead of concentrating defense on sample-specific observations at the “Actions on Objectives” or final stages of an intrusion, defenders can instead apply layered security controls targeting known adversary behaviors for a more robust defensive posture:

- Identifying and limiting directly accessible access points to a minimum necessary amount and monitoring access attempts and traffic sources for signs of anomalies.

- Implementing and enforcing multi-factor authentication (MFA) for external-to-internal and internal-to-internal remote authentication to reduce the impact of credential harvesting and reuse.

- Identify file download to and execution from common directory locations with less restricted permissions such as %TEMP% and related items. Where possible, link such observations with file characteristic details (file signature, file metadata, or other items) to produce composite, higher-confidence alerts of suspicious activity.

- Log and monitor remote process execution mechanisms, including PSExec-like capabilities but also SMB and WMI-based methods found in frameworks such as Impacket.

- Limit or track retrieval of potentially malicious payloads (such as executable files or shellcode payloads) from third-party sources and CDNs. Limit exposure where possible, or leverage analysis of payloads to identify potentially malicious items for further action.

Through a whole-of-kill-chain defensive approach, described above and illustrated in the diagram below, defenders can ensure coverage of adversary initial and intermediate intrusion stages well in advance of final objectives. In addition to ensuring that defenders can potentially catch (or mitigate) malicious activity earlier in the adversary’s operational lifecycle, such layering also ensures that when adversaries inevitably modify or change behaviors at one (or potentially more) operational stages, defenses and observations at other phases of adversary activity hold the possibility of identifying behaviors of interest.

In observing events, whether headline-grabbing incidents such as those in Ukraine or the steady drumbeat of ransomware incidents, defenders should be focused as much as possible on how to detect and mitigate intrusions as early and consistently as possible. Analysis of final-stage events, such as the WhisperGate wiper, can be of significant academic interest and enable research into adversary intentions and methodologies, but for operationally relevant network defense, such an exclusive approach simply yields far too much ground to threats to be sustainable. Instead, by layering defense and detection throughout the phases of the Cyber Kill Chain, opportunities emerge to identify adversary actions at multiple points prior to final actions — whether a destructive wiper or a disruptive ransomware event — and place the defended and monitored organization on far sounder and more robust footing.

Featured Webinars

Hear from our experts on the latest trends and best practices to optimize your network visibility and analysis.

CONTINUE THE DISCUSSION

People are talking about this in the Gigamon Community’s Security group.

Share your thoughts today