ABADBABE 8BADF00D: Discovering BADHATCH and a Detailed Look at FIN8’s Tooling

by Kristina Savelesky, Ed Miles, Justin Warner

FIN8 is a financially-motivated threat group originally identified by FireEye in January of 2016, with capabilities further reported on by Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 and root9B. This blog will introduce a new reverse shell from FIN8, dubbed BADHATCH and compare publicly reported versions of ShellTea and PoSlurp to variants observed by Gigamon Applied Threat Research (ATR). With these comparisons, we aim to show how FIN8 continues to evolve and adapt their tooling. Our goal in sharing this intelligence is to enable defenders to better prevent, discover, or disrupt FIN8’s operations and offer a greater understanding of their capabilities.

Evolving Toolsets

Gigamon ATR, along with incident response partners, observed FIN8 on numerous occasions and on each occasion collected and analyzed malicious samples for detection research. We analyzed variants of the ShellTea implant and PoSlurp memory scraper malware, designated ShellTea.B and PoSlurp.B. One of the most interesting samples analyzed appears to be a previously unreported tool, BADHATCH, that provides file transfer and reverse shell functionality.

As part of our research, Gigamon ATR reviewed previously reported samples when available, assessed public reports, and compared intelligence to our own observations from incident response engagements. Previous reporting on FIN8 indicates that initial infection typically begins with a malicious email campaign, using weaponized Microsoft Word document attachments aimed at enticing the user to enable macros. These macros execute a PowerShell command which downloads a second PowerShell script containing the shellcode of the first stage of a downloader, called PowerSniff by root9B and Unit 42, or PUNCHBUGGY by FireEye. While Gigamon ATR does not have phishing documents available for comparison, an incident response partner recovered the BADHATCH PowerShell script that, at first sight, appears comparable to PowerSniff/PUNCHBUGGY.

BADHATCH Malware

The BADHATCH sample begins with a self-deleting PowerShell script containing a large byte array of 64-bit shellcode that it copies into the PowerShell process’s memory and executes with a call to CreateThread. This script differs slightly from publicly reported samples in that the commands following the byte array are base64 encoded, possibly to evade security products. While previous analyses saw PowerSniff downloaded from online sources and executed, Gigamon ATR incident response partners recorded the attackers launching the initial PowerShell script via WMIC as visible in Figure 1.

wmic /node:“<server_name>” process call create “powershell –ep bypass –c .\<script_name>.ps1”

Figure 1: WMIC command used to launch BADHATCH PowerShell script.

The first stage of the malware then loads an embedded second stage DLL into the same memory space (using the Carberp function hash resolution routine to hide the names of API functions being used) and executes it. The use of hexadecimal constants 0xABADBABE 0x8BADF00D to locate the beginning of the embedded DLL was a common trait across all first stages of the FIN8 PowerShell scripts we analyzed (see Figure 2).

![BE BA AD AB 0D F0 AD 8B 00 66 00 80 4D 38 5A 90 æ∫.´....f..M8Z.

38 03 66 02 04 09 71 FF 81 B8 C2 91 01 40 C2 15 8.f...qˇ.∏¬..@¬.

C6 C0 09 1C 0E 1F BA F8 00 B4 09 CD 21 B8 01 4C ∆¿....∫¯.¥.Õ!∏.L

C0 0A 54 68 69 73 20 0E 70 72 6F 67 67 61 6D 87 ¿.This .proggam.

63 47 6E 1F 4F 74 E7 62 65 AF CF 75 5F 98 69 06 cGn.OtÁbeØœu_.i.

44 4F 7E 53 03 6D 6F 64 65 2E 0D 89 0A 24 4C 44 DO~S.mode....$LD sub ecx, edi

cmp dword ptr [rax], 0ABADBABEh

mov rdx, rax

jnz short loc_24CBF8D0086

cmp dword ptr [rax+4], 8BADF00D

jz short loc_24CBF8D008E](https://blog.gigamon.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/figure2-BADHATCH-1024x137-1.png)

Once executed, depending on the session ID, the embedded DLL either APC injects into a svchost.exe process (launched with svchost.exe -k netsvcs), or injects into explorer.exe (using the ToolHelp32 API functions and RtlAdjustPrivilege to enable SeDebugPrivilege). The malware creates a local event object, with the hardcoded name Local\{45292C4F-AABA-49ae-9D2E-EAF338F50DF4}, which is used similarly to a mutex (to ensure only one copy is running at a time).

On startup, and every 5 minutes thereafter, the sample beacons to a hardcoded command and control (C2) IP (149.28.203[.]102) using TLS encryption, and sends a host identification string derived from several system configuration details and formatted as %08X-%08X-%08X-%08X-%08X-SH. Only the one hardcoded IP address and no C2 domains were observed. Upon connecting back to the C2 server and sending the system ID, the shell will offer the banner shown in Figure 3, with the OS version and bitness as well as the hostname values filled in.

----------------------------------------

* SUPER REMOTE SHELL v2.2 SSL

----------------------------------------

OS: %s SP %d %s

HOSTNAME: %s

Press i+enter to impersonate shell or just press enter

Figure 3: banner of the BADHATCH reverse shell.

The shell even includes a small bit of online help with troubleshooting suggestions (displayed in Figure 4) if there are issues with launching the cmd.exe process the shell uses for command execution.

Logon failure: unknown user name or bad password.

Logon failure: user account restriction. Possible reasons are blank passwords not allowed, logon hour restrictions, or a policy restriction has been enforced.

The trust relationship between this workstation and the primary domain failed.

The service cannot be started, either because it is disabled or because it has no enabled devices associated with it.

Run 'sc start seclogon' if you can ;)

Failed to execute shell, error %u

Figure 4: Plaintext error messages present in the strings of the BADHATCH DLL.

An option for impersonating a specific user via the Windows APIs is given, but both execution paths will start a cmd.exe process for command execution. Upload and download functions are available, and the shell looks for those commands, as well as a ‘terminate’ command, before sending any input to the cmd.exe process.

BADHATCH uses the Windows IO Completion Port APIs and low-level encryption APIs from the Security Support Provider Interface to implement an asynchronous TLS-wrapped TCP/IP channel. As a side effect of this implementation, port 3885 will be opened and bound on localhost. The malware connects back to itself on this port and uses this as a loopback transmission channel in the course of encrypting and transferring data between threads. Internally, this mechanism uses CompletionKeys of ’nScS’ and ‘rScS’. These keys are used to track which IO operations have completed and identify the sender/receiver threads that handle the shell communication.

Besides the networking behavior, BADHATCH appears to be considerably different from PowerSniff in that it contains no methods for sandbox detection or anti-analysis features apart from some slight string obfuscation. It includes none of the environmental checks to evaluate if it is running on possible education or healthcare systems and has no observed built-in, long-term persistence mechanisms. Below, Table 1 summarizes the differences between PowerSniff, PUNCHBUGGY, and BADHATCH.

| Shared Component | root9B PowerSniff | Unit 42 PowerSniff | VirusTotal PUNCHBUGGY | ATR BADHATCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA-256 | Hash not provided in report | Hash for maldoc provided in report | 5024306ade133b0 ebd415f01cf64c23 a586c99450afa9b7 9176f87179d78c51d | c5642641064afc7 9402614cb916a1e 3bd5ddd493277 9709e38db64d6 cc561cd5 |

| Infection vector is a spearphishing email with an attached maldoc that downloads a PowerShell stager | Unknown, observed being launched via WMIC | |||

| Target architecture is 32- or 64-bit | Observed 64-bit | |||

| First stage loads and runs shellcode in memory that loads a DLL second stage | 0xABADBABE 0x8BADF00D checks to find embedded DLL | 0xABADBABE 0x8BADF00D checks to find embedded DLL | ||

| Use of Carberp function hash resolution routine in shellcode to find API functions | Unmentioned in report | Same hashes and algorithm as BADHATCH | Same hashes and algorithm as PUNCHBUGGY | |

| Embedded DLL decrypts strings using algorithm with seed 0xDDBC9D5B, multiplier 0x19660D, increment 0x3C6EF35F | Unmentioned in report | Same seed and constants as PUNCHBUGGY | Same seed and constants as Unit 42 PowerSniff sample | Not observed |

| Includes methods for sandbox detection | Slightly different than Unit 42 sample/PUNCHBUGGY | Identical to PUNCHBUGGY | Identical to Unit 42 sample | None observed |

| Ability to write DLL to %%userprofile%%\AppData\LocalLow\%u.db and run via rundll32 | Not observed | |||

| Ability to write an executable and run it | Unmentioned | Not observed | ||

| Ability to write a DLL and load into calling process with LoadLibraryW | Unmentioned | Not observed | ||

| Performs HTTP requests with user agent of Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT %u.%u%s) | Contacts C2 via HTTP, user agent unspecified in report | Contacts command and control IP via TLS over 443 every 5 minutes | ||

| Persistence | Ability to write a DLL and add it to HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\ Control\Session Manger\AppCertDlls for persistence | Persistence unspecified | No observed registry modifications | No observed persistence |

| Memory string similarity | Similar to PUNCHBUGGY and Unit 42 PowerSniff | Seem identical to PUNCHBUGGY, similar to root9B PowerSniff | Seem identical to Unit 42 PowerSniff, similar to root9B PowerSniff | Very different from other samples |

| Ability to inject into explorer.exe | Unmentioned | Unobserved | ||

| Ability to spawn and inject into svchost.exe process if sessionID = 1 | Unmentioned | Unmentioned | Unobserved | |

| Ability to download/uploaded files to/from user-supplied path | Unmentioned | Unmentioned | Unobserved | |

| Ability to start interactive shell | Unmentioned | Unmentioned | Unobserved | |

| Ephemeral localhost port 3885 usage | Unmentioned | Unmentioned | Unobserved | |

| Command and control | vseflijkoindex[.]net vortexclothings[.]biz unkerdubsonics[.]org popskentown[.]com | supratimewest[.]com letterinklandoix[.]net supratimewest[.]biz starwoodhotels[.]pw oklinjgreirestacks[.]biz www.starwoodhotels[.]pw brookmensoklinherz[.]org | supratimewest[.]com letterinklandoix[.]net supratimewest[.]biz starwoodhotels[.]pw oklinjgreirestacks[.]biz www.starwoodhotels[.]pw brookmensoklinherz[.]org | 149.28.203[.]102 |

ShellTea.B Implant

ShellTea is a memory-resident implant that includes multiple methods for downloading and executing additional code and can install persistence via the registry. Its primary use case appears to be serving as a stealthy foothold in the victim network and deploying additional payloads.

During two previous incident response engagements involving FIN8, response partners recovered registry keys containing hexadecimal-encoded data and corresponding PowerShell scripts. Gigamon ATR discovered these to be persistence artifacts of ShellTea variants, with a few differences from root9B’s ShellTea sample. Table 2 presents a comparison of differentiating features between ShellTea and ShellTea.B.

| root9B ShellTea | ATR ShellTea.B |

|---|---|

| Hash not provided in report | Shellcode from registry: 385538451e59f630db6f1b 367aacfdbb85b7d730210 fc6d5b2bee7037f0362a5 |

| PowerShell script waits five seconds for thread to complete | PowerShell script includes Start-Sleep 2; then waits for one minute for thread to complete |

| Uses a custom function resolver with 4-byte hashes and seed 0x463283F5, multiplier 0x19660D, increment 0x3C6EF35F | Uses a custom function resolver with 4-byte hashes and seed 0x463283F5, multiplier 0x19660D, increment 0x3C6EF35F |

| Use of Ws2_32.dll exports for network functionality (connect, send, etc.) | Use of wininet.dll exports for network functionality (InternetConnectA, HttpSendRequestA, etc.) |

| Connects to command and control over port 443 using a custom binary protocol with XTEA encryption in CBC mode, can communicate through proxies via CONNECT | Communicates with command and control servers using HTTPS POST requests, with XTEA-encrypted payload in the body (see Figure 5 for headers) The command and control servers utilized a standard self-signed “Internet Widgets” Apache TLS certificate |

| C2 domains include: neofilgestunin[.]org verfgainling[.]net straubeoldscles[.]org olohvikoend[.]org menoograskilllev[.]net asojinoviesder[.]org | C2 domains include: moreflorecast[.]org preploadert[.]net troxymuntisex[.]org nduropasture[.]net |

| No encoded DNS traffic mentioned | Encoded DNS requests to generated subdomains of nduropasture[.]net |

POST

json/

Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/4.0

Accept: application/octet-stream

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

Connection: close

Figure 5: Strings output of hardcoded HTTP POST headers used in ShellTea.B communications, note the missing right parenthesis of the user agent string.

In addition to the HTTPS channel, ShellTea.B uses DNS to communicate with C2 infrastructure. Small messages, usually 39 bytes, are encoded in the subdomain field of DNS A-record queries. These messages are composed of several pieces of internal state encoded in the character space “abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz012345”. The state transmitted includes an internal PRNG seed as well as several hardcoded values embedded in the malware at compile time, while the query responses consist of single IP addresses. The DNS channel is initiated from within several nested loops, that can cause repeated lookups depending on the IP address. If the IP doesn’t conform to several value checks, the inner loop will run again after a 30 second delay, up to 3 times. Iterations of the inner loop are controlled by checking if the IPs first octet plus 7 is not equal to the second octet, or if the fourth octet modulo 10 does not result in 0, 1, 2, or 3 (see Figure 6). If the inner loop terminates while the result of the modulo is greater than 0, the outer loop will run again after a delay based on the modulo value, causing the cycle to begin again. NOTE: On initialization, this DNS channel will be active before the HTTP channel.

The differences in communication protocols between ShellTea and ShellTea.B suggest minor changes to this element of the FIN8 attack chain, possibly to adapt to target environments by blending in with other HTTPS or DNS traffic in lieu of a more suspicious custom protocol.

PoSlurp.B Scraper

The final, perhaps most important component in the FIN8 toolkit, is the one that actually retrieves credit card numbers as they pass through payment card processing systems. Credit card numbers are 15 or 16 digits long and conform to the Luhn algorithm. This algorithm defines valid credit card numbers, and most scrapers check card numbers against it. Notably, PoSlurp does not run the Luhn algorithm on card numbers it collects. Verification may be performed offline, after the exfiltration of the card data, but either way, FIN8 knows the environment and PoSlurp targets the card processing software directly for scraping rather than arbitrarily scraping other process memory.

During previous incident response engagements involving FIN8, response partners also recovered POS memory-scraping samples: one, an executable binary that appears to be a 32-bit version of the PoSlurp malware reported by root9B (reported as PUNCHTRACK by FireEye), and another, a PowerShell script highly similar to the BADHATCH PowerShell script. This script was also observed being executed via WMIC, illustrated in Figure 7.

wmic /node:”@t.txt” /user:”<username>” /password:”<password>” process call create “powershell -ep bypass –c c:\users\<admin_user>\appdata\local\temp\<script_name>.ps1”

Figure 7: WMIC command used to launch the PoSlurp.B script.

Like the BADHATCH script, this script base64 decodes and executes further commands which load a byte array of shellcode into memory and begin execution. The PowerShell script is then moved to a temporary file before being overwritten with a copy of the Regedit executable and then deleted. True to the previously analyzed first stage scripts, the shellcode uses the Carberp function hash resolution routine to locate an embedded DLL by parsing for the same hexadecimal constants, loads the DLL into memory, and executes it. Unlike the notable use of low-level API functions and anti-analysis techniques in PoSlurp, PoSlurp.B’s first stage simply calls VirtualAlloc, LoadLibrary, and GetProcAddress to dynamically resolve imported functions, without other tricks to thwart analysis. Where PoSlurp and PUNCHTRACK arguments are passed in as part of the command line, PoSlurp.B arguments are passed in an environment variable and are pipe-delimited instead of hash- or asterisk-delimited (see Figure 8).

$env:PRMS = “i|<inject_process_name>|<scrape_process_name>|t|2800|”;

Figure 8: Pipe-delimited PoSlurp.B arguments passed in an environment variable in the PowerShell script.

Major functional differences in PoSlurp.B include the ability to:

- Inject into the target process given an ‘i’ argument.

- Create a svchost netsvcs process and APC inject the main loop given an ‘s’ argument.

- Run the main loop without injection given a ‘p’ argument.

The PUNCHTRACK sample that we analyzed (downloaded from VirusTotal) also had the ability to create and inject into a svchost process, though it did so regardless of command line arguments.

Additionally, the call to DeleteFile that cleaned up old output files has been removed. Incident response partners captured these actions being performed manually, show in Figure 9.

for /F %i in (<filename>.txt) DO attrib -h \\%i\c$\users\<local_admin_user>\appdata\local\temp\<filename>.tmp

for /F %i in (<filename>.txt) DO net use \\%i\c$ /user:%i\<username> <password>

for /F %i in (<filename>.txt) DO copy \\%i\c$\users\\<local_admin_user>\appdata\local\temp\<filename>.tmp %i.tmp

for /F %i in ((<filename>.txt) DO del \\%i\c$\users\\\<local_admin_user>\appdata\local\temp\\<filename>.tmp

Figure 9: Commands to manually unhide, copy, and delete encrypted PoSlurp.B log files.

The following table (Table 3) provides a comparison between features observed in two versions of PoSlurp, a PUNCHTRACK sample downloaded from VirusTotal, and PoSlurp.B.

| Shared component | root9B PoSlurp | ATR PoSlurp | VirusTotal PUNCHTRACK | ATR PoSlurp.B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHA-256 | Hash not provided in report | cc952950a73909a 655044dbb87f85f 66d44d1d4e3a1e0 96777bbc938a62bd 080 (link) | ffc133ea83deac 94bce5db1a4202 57304931e6d3cfb 82c6d9e50a2a98 f43d310 (link) | 8c6fe4c8b000e87 b756d5fd0b53d3e 230ceafa8928851a 91dac42445c0bab8e3 |

| Invocation | wmic /node:”@targets.txt” process call create “cmd /c [PoSlurp_filename].exe TARGET1.EXE #TARGET2.exe*1234*winlogon.exe” | cmd /c psv.exe TARGET1.EXE #TARGET2.EXE*1400*winlogon.exe | Takes 3 args: PUNCHTRACK filename (psvc.exe), POS target process, and timeout | wmic /node:”@t.txt” /user:”<username>” /password:”<password>” process call create “powershell –ep bypass –c c:\users\<admin_user>\appdata\ local\temp\<script_name>.ps1” $env:PRMS = “i|wininit.exe|<scrape_process_name> |t|2800|”; |

| Target architecture | 64-bit judging by screenshots | 32-bit | 32-bit | 64-bit |

| Use of RtlWriteMemoryStream for constants, uses custom API hashing algorithm for resolving functions | Not observed | |||

| Use of Carberp function hashing code to resolve imports | ||||

| First stage byte length | 6610 bytes | 6608 bytes | 6368 bytes | 7186 bytes |

| 0xABADBABE and 0x8BADF00D checks in first stage to find start of embedded DLL | Not mentioned | |||

| Uses ZwAllocateVirtualMemory LdrLoadDll and LdrGetProcedureAddress | Same hashes as PUNCHTRACK | Same hashes as psv.exe | Uses VirtualAlloc LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress | |

| CreateToolhelp32Snapshot to find processes | ||||

| RtlAdjustPrivilege (SE_DEBUG) + WrtieProcessMemory + RtlCreateUserThread to inject into target process | Injects into target given ‘i’ | |||

| Creates svchost netsvcs process and APC injects main loop | Not mentioned | Not observed | Always | Only when given ‘s’ |

| Able to run main loop without injection | Not mentioned | Not observed | Not observed | When given ‘p’ |

| Deletes old log files | Calls DeleteFileW before running scraper | Calls DeleteFileW before running scraper | Does not call Sleep or DeleteFile before scraping | |

| Scans target process’s memory every 5 seconds until timeout, encrypts card data and saves |

Stitching Together the Pieces

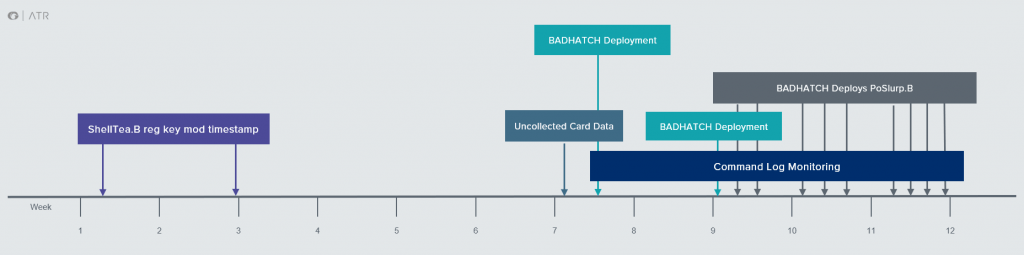

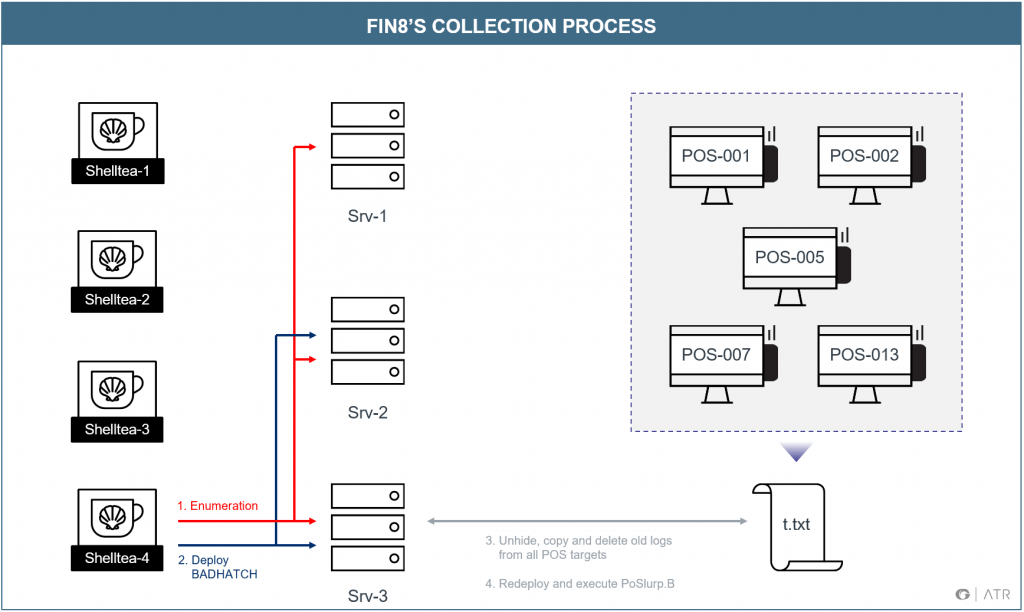

Our analysis is the result of the combined efforts of Gigamon ATR and our incident response partners. With shared data from one recent engagement, we put together a more complete picture of the role each tool plays in FIN8’s kill chain. The BADHATCH, ShellTea.B, and PoSlurp.B samples detailed above were recovered from forensic analysis during incident response. While our data regarding the entire attack is incomplete, the analysis of evidence obtained revealed an interesting picture of FIN8’s workflow, displayed in Figure 10.

Our response partner’s timeline began with observed modifications to suspicious registry keys, which Gigamon ATR analyzed and determined to be containing persistence mechanisms for the ShellTea.B memory implant. Logs also revealed two PowerShell scripts launched via WMIC with compromised credentials. We found these scripts to be the PowerShell stagers for BADHATCH and PoSlurp.B. Even though multiple workstations had ShellTea.B persistence keys in the registry, the attackers operated predominately from a single workstation. From the ShellTea.B infected workstation, they enumerated three different servers on the network and deployed the BADHATCH reverse shell to two, but ultimately were observed only using one server to communicate with POS devices (see Figure 11).

After successfully reaching their objectives, interactions increased, with almost daily sessions featuring BADHATCH deployments. Card data was removed from the POS hosts, collected on the infected IT server, and staged there for exfiltration. The repetitive scraping and collection process was:

- Deploy the (non-persistent) BADHATCH reverse shell to the server

- From the server, issue commands to each POS system in a target list to

- Unhide the hidden log of encrypted card data

- Copy the log back to the server

- Delete the old log file

- Execute the PoSlurp.B PowerShell script

In the first weeks of the command log, PoSlurp.B was not seen being deployed, even though uncollected card data existed on one of the POS machines with an earlier timestamp. Only two attacker sessions were seen, performing some basic network recon using ping and netstat, prior to deploying BADHATCH, with commands illustrated in Figure 12.

wmic /node:"<IT_server>" process call create "cmd /c ping <ip_address> > out.txt"

wmic /node:"<IT_server> " process call create "cmd /c netstat -f > out.txt"

Figure 12: WMIC commands used for reconnaissance.

Although the command logs only captured the later stages of the operation, analysis of this data proved vital for understanding the relationships between the attacker’s components, as well as how they moved and interacted in the environment. Large variations in timing data demonstrated that actions were performed by humans, rather than automated tasks. This data also revealed some unexpected details: it turns out threat actors make mistakes too! Multiple command errors were observed, including a session where the operator attempted to run a command from the wrong directory multiple times before getting it right. Another session featured commands accidentally run from the wrong machine before being properly executed on the intended target.

At the end of the day, the actors behind FIN8 are human and clearly fallible. While they may make rapid improvements to tools and procedures, we hope the technical and operational information shared here will help other organizations detect and disrupt FIN8 operations.

Learn more about financially motivated threats in our newest report: A Look Inside Financially Motivated Attacks and the Active FIN8 Threat Group

Gigamon Applied Threat Research would like to acknowledge Charles River Associates, a Gigamon Insight incident response partner, with a special thank you to Peter Seddon, Andrew Fry, Kevin Kirst, and Geoff Fisher, for their contributions to this research.

Appendix: Detection Strategies

There are several unique opportunities for detection across the operational lifecycle and artifacts generated by FIN8’s toolset. Indicators vary from recurring observed techniques to campaign-specific atomic indicators. This section draws on information from the analysis of each sample and observations from the live incident response engagement to build detection strategies for future use.

Observations & Signatures

During our engagements with FIN8, we saw several patterns in their behavior that serve as useful observations but are not unique enough or associated with malicious activity directly enough to be alert worthy. Checking for these characteristics and adding context from the environment should produce investigable data:

- Default self-signed certificates on low reputation infrastructure – FIN8 infrastructure utilized the default self-signed “Internet Widgets” Apache TLS certificate as well as newly-registered domains and common VPS-based hosting providers. These observations can be used to hunt FIN8 and many other threat actors.

- Periodic connections – Identifying periodic connections can help detect automated behaviors, such as the 5-minute timing of callbacks from BADHATCH and the periodic DNS and HTTPS traffic of ShellTea.B.

- Newly observed one-to-many RPC/WMI interactions – FIN8 makes heavy use of Windows file sharing and WMIC to distribute and execute its tooling. Spotting these actions can help identify infected hosts at various stages of an operation.

- Encoded DNS Traffic – As detailed above, ShellTea.B utilizes a DNS-based communication channel to contact its C2 servers. A-record queries are generated with high-entropy subdomains that can be matched by a regex like “[a-z0-5]{39,42}”. The responses to these queries would also stand out as being distributed among random IP blocks.

Additionally, while signature-based detection tends to be prone to evasion, it is a valuable part of a comprehensive detection strategy, particularly with actors that reuse infrastructure and tools between engagements. With this set of malware, signature-based network detection is complicated by the use of encryption, but signatures are provided for cases where SSL/TLS termination is in use. The following signatures can identify the tools discussed in this blog:

rule FIN8_abadbabe

{

meta:

author = "Kristina Savelesky – Gigamon ATR"

description = "Hexadecimal constants used in FIN8 unembedding"

last_modified = "June 27, 2019"

strings:

$abadbabe= "0xbe,0xba,0xad,0xab"

$8badf00d = "0x0d,0xf0,0xad,0x8b"

$hex = { be ba ad ab 0d f0 ad 8b }

condition:

$hex or ($abadbabe and $8badf00d)

}

alert tcp $HOME_NET 1024: -> $EXTERNAL_NET 443 (msg:"GIGAMON_ATR COMMAND_AND_CONTROL BADHATCH Check-in"; flow:established, from_client, no_stream; dsize:64; content:"-SH"; offset:44; depth:3; pcre:"/[0-9A-F]{8}-[0-9A-F]{8}-[0-9A-F]{8}-[0-9A-F]{8}-[0-9A-F]{8}-SH/"; content:"|02 09 01|"; offset:52; depth:3; flowbits:set,ATR.BADHATCH.check-in; classtype:trojan-activity; sid:2900366; rev:3;)

alert tcp $HOME_NET 1024: -> $EXTERNAL_NET 443 (msg:"GIGAMON_ATR COMMAND_AND_CONTROL BADHATCH Banner"; flow:established, from_client; dsize:>100; flowbits:isset,ATR.BADHATCH.check-in; content:"|2a 20|SUPER|20|REMOTE|20|SHELL|20|v2|2e|2|20|SSL"; classtype:trojan-activity; sid:2900367; rev:2;)

reject http $HOME_NET any -> $EXTERNAL_NET any (msg:"GIGAMON_ATR COMMAND_AND_CONTROL ShellTea.B User Agent POST Request"; content:"POST"; http_method; depth:4; content:"json/"; http_uri; content:"Mozilla/4.0 (compatible|3B| MSIE 8.0|3B| Windows NT 6.1|3B| Trident/4.0"; http_user_agent; offset:0; depth: 62; content:!")"; http_user_agent; distance:0; within:1; content:"Accept|3a 20|application/octet-stream"; http_header; content:"Content-Type|3a 20|application/octet-stream"; http_header; distance: 0; content:"Connection|3a 20|close"; http_header; distance:0; classtype: trojan-activity; sid:1; rev:1;)

Atomic Indicators

Atomic indicators are a valuable component of a detection strategy, particularly in situations when the actor has been known to reuse infrastructure. Due to the use of shared hosting, IP address indicators will vary in usefulness. The atomic indicators in Table A1 were observed in our analysis.

| Indicator | Type | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| c5642641064afc79402614cb916a1e3bd5 ddd4932779709e38db64d6cc561cd5 | SHA256 | BADHATCH |

| 149.28.203[.]102 | IP Address | BADHATCH |

| Local\{45292C4F-AABA-49ae-9D2E-EAF338F50DF4} | Event String | BADHATCH |

| subarnakan[.]org | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| subarnakan[.]org | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| asilofsen[.]net | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| manrodoerkes[.]org | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| ashkidiore[.]org | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| druhanostex[.]net | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| kapintarama[.]net | Domain | ATR ShellTea |

| 385538451e59f630db6f1b367aacfdbb 85b7d730210fc6d5b2bee7037f0362a | SHA256 | ShellTea.B |

| moreflorecast[.]org | Domain | ShellTea.B |

| 198.199.105.192 | IP | ShellTea.B Resolution |

| preploadert[.]net | Domain | ShellTea.B |

| 104.248.9.143 | IP | ShellTea.B Resolution |

| troxymuntisex[.]org | Domain | ShellTea.B |

| nduropasture[.]net | Domain | ShellTea.B |

| 8c6fe4c8b000e87b756d5fd0b53d3e 230ceafa8928851a91dac42445c0bab8e3 | SHA256 | PoSlurp.B |

| %TMP%\wmsetup.tmp | File path | PoSlurp.B |

ATT&CK Mapping

ATT&CK is a framework developed by MITRE and widely used by intelligence communities to characterize and model TTPs used by threat actors and their tooling. In Table A2 below, we map the TTPs observed in BADHATCH, ShellTea.B, and PoSlurp.B, as well as operational techniques, to ATT&CK techniques.

| Stage | Techniques observed in: | |

|---|---|---|

| BADHATCH | ||

| ShellTea.B | ||

| PoSlurp.B | ||

| Operationally | ||

| Collection | Data from Local Systems (T1005) | |

| Data Staged (T1074) | ||

| Command and Control | Commonly Used Port (T1043) | |

| Custom Command and Control Protocol (T1094) | ||

| Custom Cryptographic Protocol (T1024) | ||

| Data Encoding (T1132) | ||

| Standard Cryptographic Protocol (T1032) Obfuscation (T1001) | ||

| Multiband Communication (T1026) | ||

| Remote File Copy (T1105) | ||

| Standard Application Layer Protocol (T1071) | ||

| Standard Cryptographic Protocol (T1032) | ||

| Uncommonly Used Port (T1065) | ||

| Defense Evasion | Access Token Manipulation (T1134) | |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information (T1140) | ||

| Execution Guardrails (T1480) | ||

| File Deletion (T1107) | ||

| File Permissions Modification (T1222) | ||

| Hidden Files and Directories (T1158) | ||

| Modify Registry (T1112) | ||

| Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027) | ||

| Process Injection (T1055) | ||

| Scripting (T1064) | ||

| Valid Accounts (T1078) | ||

| Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion (T1497) | ||

| Discovery | Network Share Discovery (T1135) | |

| Process Discovery (T1057) | ||

| Query Registry (T1012) | ||

| Remote System Discovery (T1018) | ||

| Security Software Discovery (T1063) | ||

| System Information Discovery (T1082) | ||

| System Network Configuration Discovery (T1016) | ||

| System Network Connections Discovery (T1049) | ||

| System Owner/User Discovery (T1033) | ||

| System Time Discovery (T1124) | ||

| Virtualization/Sandbox Evasion (T1497) | ||

| Execution | Command-Line Interface (T1059) | |

| Execution through Module Load (T1129) | ||

| PowerShell (T1086) | ||

| Scripting (T1064) | ||

| Service Execution (T1035) | ||

| Windows Management Instrumentation (T1047) | ||

| Exfiltration | Data Encrypted (T1022) | |

| Exfiltration over Command and Control Channel (T1041) | ||

| Initial Access | Valid Accounts (T1078) | |

| Lateral Movement | Remote File Copy (T1105) | |

| Remote Services (T1021) | ||

| Windows Admin Shares (T1077) | ||

| Persistence | Hidden Files and Directories (T1158) | |

| Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder (T1060) | ||

| Valid Accounts (T1078) | ||

| Privilege Escalation | Access Token Manipulation (T1134) | |

| Process Injection (T1055) | ||

| Valid Accounts (T1078) |