WannaCry: Key Points of Interest

What We Know: Let’s Make a List

- WannaCry ransomware is a variant of WanaCrypt0r, which leverages the ETERNALBLUE SMBv1 exploit to infect connected systems.

- WannaCry was enabled by Equation Group exploits that were stolen and released by a hacker group called the Shadow Brokers.

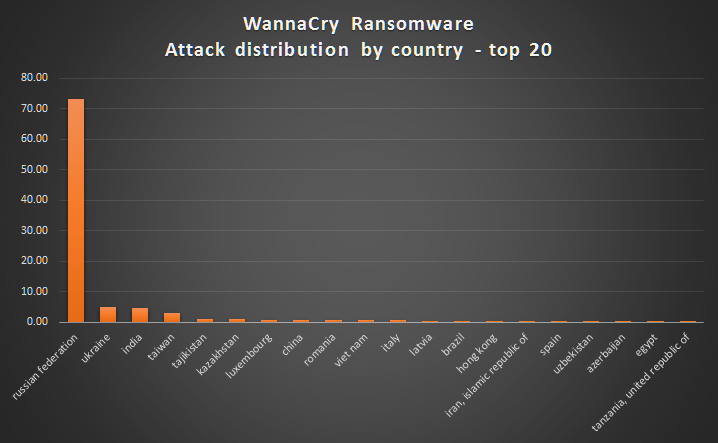

- At least 100 countries were affected by the WannaCry ransomware, primarily Russia, India, the United Kingdom and other European countries.

- Three bitcoin wallets associated with WannaCry 2.0 ransomware had received just under $86,000 USD in payments as May 18.

- The single largest bitcoin transaction associated with the campaign appears to have been made using BTC-e for approximately $3,300 (equal to decrypting 11 computers).

- No funds appear to have been removed from the bitcoin wallets as of May 17.

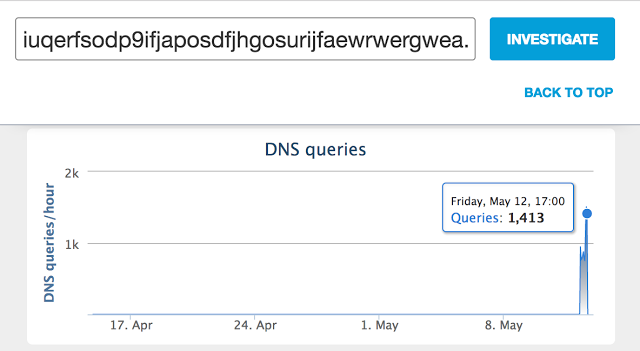

- The initial spread of WannaCry was halted when 22-year-old security researcher @malwareTechBlog found a domain-based kill switch within the code. By registering the domain iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com, he activated the kill switch for inadvertently saved the world. His cost: $10.69.

- Consensus among security researchers is that the cybercriminals behind WannaCry didn’t intend for such a widespread attack and don’t possess the expertise to properly enable or protect the malware from reverse engineering.

One for the History Books

The WannaCry ransomware attack is one for the history books. It’s likely the worst, most widespread cyberattack to hit the Internet in years and, possibly, the first indiscriminate and globally ubiquitous attack to damage critical real-world services like hospitals and transportation systems and put real lives in danger.

Yet, despite the far-reaching scope of the attack—reportedly infecting 200,000 systems across 150 countries as well as inadvertently inflicting substantial cyber-physical damage—it seems unlikely to have been the work of cybercriminals. In fact, most security researchers have concluded that it was more likely a cyber-heist that got out of hand, punctuated by amateur mistakes at practically every point of the attack’s planning and execution.

Nevertheless, WannaCry ransomware is unique for two main reasons. First, it’s a ransomware worm that spreads at a volume and velocity never before witnessed. Second, it leveraged a recently patched exploit in older versions of Microsoft Windows that had been stolen from the NSA. No doubt, this second piece will spark a great deal of policy and legal debate regarding exploit hoarding, backdoors and encryption.

An attack of this magnitude and impact that was so poorly executed certainly raises many questions for investigators and provided a sobering teachable moment: What would have happened if highly disciplined and professional cybercriminals or a state actor had orchestrated and executed the attack?

“Lessons Learned” for the Hackers

If Ocean’s Eleven,Twelve, Thirteen, The Italian Job, The Thomas Crown Affair and all other classic heist movies have taught us anything, it’s that when it comes to a pulling off a major criminal venture, preparation and timing is everything.

So what lessons have the hackers likely learned? For starters, if you’re going to launch a major cyber-attack against corporate and institutional targets, Wednesday morning—as opposed to Friday afternoon—might be a better and more profitable choice.

Many people have asked me why the damage was seemingly limited to certain parts of the world, with some countries suffering greatly while others went practically unscathed. My best answer to date is twofold:

- The countries with a high prepense towards the use of pirated software were among the hardest hit.

- As the WannaCry attack began to spread, a good portion of Asia had already left work for the day and much of North America was only just getting into the office as the kill switch was triggered, meaning that anyone living in the time zones in between (e.g., Europe) was particularity vulnerable. Countries such as Russia, which fell into both categories, were the hardest hit.

While the geographic spread of the attack was somewhat scattered and random in nature, there were significant infections reported throughout Russia, which is quite remarkable considering that Russia is often exempt from ransomware campaigns.

From this data, I drew two hypotheses: One, the sheer number of infections in Russia likely indicates that the attackers are located in some other country. Two, the attackers are really inexperienced and likely intentionally halted further attacks, which is why we are not seeing a substantial second wave. And c’mon, think about it. Committing high-profile, financially destructive attacks against Russia might just be a cybercriminal career-limiting move.

Did the Attack Go as Planned?

Um, not so much. Assuming the attackers were looking to make substantial profits, it certainly did not go as planned and I’d go so far as to say it was a complete failure. This spectacularly innovative, extremely destructive, highly visible (meaning both media and law enforcement) attack produced one of the lowest profits in the history of ransomware attacks. In fact, the attackers might have made more money robbing a brick-and-mortar bank in a major city with a banana in their pocket than with this scheme. Again, as of May 17 at 9:00 p.m. EST, they had collected a mere $81,620.52 USD. To put this into perspective, while active, a 2015 ransomware attack known as Angler raked in an estimated $60 million USD/year.

The only real success of the WannaCry attack was the massive scale it achieved in such a short time and, frankly, the crooks even bungled that. It got off to a spectacular start, spreading at an enormous rate. Cisco researchers first observed requests for one of WannaCry’s kill switch domains (iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea[.]com) starting at 07:24 UTC, then rising to a peak of just over 1,400 nearly 10 hours later.

Source: http://blog.talosintelligence.com/2017/05/wannacry.html

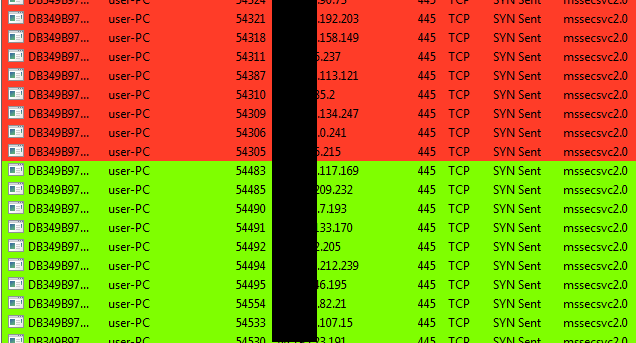

WannaCry ingeniously uses the MS17-010 exploit to spread to other machines through NetBIOS. It appears to generate a list of internal IPs, including random IP addresses not limited to the local network; propagate autonomously both within an infected organization; and then spread outbound to other vulnerable systems on the Internet if sites allow NetBIOS packets from outside networks. This could be one reason why many people are unsure about the initial infection vector of the malware, thus deepening the WannaCry mystery.

The following is an example attempt at propagation:

Source: https://securingtomorrow.mcafee.com/20170514-wannacry-1/

Needless to say, this is unique, innovative behavior. But, even judging WannaCry’s success based on its ability to spread quickly, the attack is again likely to be deemed a failure by most security researchers. The attackers built into the code a manual kill switch that was quickly and easily reverse engineered and triggered. This allowed the world a considerable amount of time to patch systems before a second wave could emerge. When the second wave did come, it, too, included a hardcoded kill switch that, once again, was quickly and easily reverse engineered and triggered.

Now why would they do that? Some researchers have speculated that the kill switch was designed purposely as a means to avoid detection via sandboxing (meaning the code is running on a virtual test machine). Others point out that the whole thing did so much damage and was so poorly executed that it might not have been motivated for profit at all. Support for this argument has increased since the Shadow Brokers (who released the initial exploits that enabled WannaCry) have now announced they plan to launch a “monthly exploit as a service”—sort of a wine club subscription business model for exploits that can be weaponized by cybercriminals.

So was WannaCry simply a proof of concept or market validation? Possibly, but unlikely in my opinion.

What Will the Hackers Try to Avoid?

If this group of hackers is going to stay in business, they will need to learn that automation is key to scaling a business and to avoid manual processes that impact their money-making ability.

Matthew Hickey, a researcher at London-based security firm Hacker House, determined that WannaCry doesn’t automatically verify that a victim has paid the $300 bitcoin ransom by assigning them a unique bitcoin address as have other successful ransomware campaigns in the past. With three hardcoded bitcoin addresses (and one from a previous iteration of the ransomware) used to receive incoming payments, there are no identifying details that could help automate the decryption process. Instead, the criminals, assuming they intended to honor the ransom payment and decrypt the users files, likely will have to manually determine which computer to decrypt as ransom payments come in. This degree of manual process simply does not scale.

And when it comes to running a successful cybercriminal ransomware business, it might surprise you to know that excellent customer service matters. Most highly profitable ransomware campaigns include customer support that is easy to contact and extremely helpful to assist victims with the process of paying the ransom and decrypting their files. In the case of WannaCry, the only option to contact the malware creators is a “contact us” option on the ransom note screen that doesn’t appear to function or is not being monitored.

Why does customer support matter? Because a successful ransom scheme is a built on trust. Victims will only pay the ransom if they have at least some degree of confidence that the criminal will fulfil the contract— a contract based on the principals of offer, acceptance and consideration. If victims no longer have confidence that they will be able to restore their data after paying the ransom, they simply will not pay. Once word gets out that the criminals are not honoring their side of the bargain, it breaks the entire trust model that makes ransomware work. The fact that we’re not hearing of many, if any, successful data restorations resulting from paid ransoms may validate this theory to some degree.

Lastly, the WannaCry perpetrators didn’t put a great deal of thought into their laundering plan. Why go to all that trouble if you can’t access and spend the money? While many people believe that bitcoin it completely anonymous, it’s not. Using only three hardcoded bitcoin addresses makes it incredibly easy for security researches and law enforcement to track any attempt to anonymously cash out WannaCry profits as all bitcoin transactions are visible on a public ledger, known as the blockchain. You can check them yourself. The addresses are:

- https://blockchain.info/address/13AM4VW2dhxYgXeQepoHkHSQuy6NgaEb94

- https://blockchain.info/address/12t9YDPgwueZ9NyMgw519p7AA8isjr6SMw

- https://blockchain.info/address/115p7UMMngoj1pMvkpHijcRdfJNXj6LrLn

And the fourth bitcoin address associated with an earlier campaign using version 1.0 of the WannaCry ransomware: https://blockchain.info/address/1QAc9S5EmycqjzzWDc1yiWzr9jJLC8sLiY

Where Might They Make Adjustments?

I think the WannaCry creators wasted a huge opportunity and they likely know it. At this point, they have lost the element of surprise. The world has had time to patch systems and while many computers around the globe continue to be infected, the perpetrators aren’t making any money and any attempt to access paid funds might inadvertently exposes them to attribution or even arrest.

As of May 17, the funds have not been moved from any of the hardcoded addresses, meaning that as of yet, there’s no money trail for law enforcement to follow.

What Can We Expect to Happen Next?

All kinds of things. It’s not just the WannaCry attackers that learned lessons from all of this; the rest of the cybercriminal world was watching and learning, too.

WannaCry broke new ground in many ways. Inexperienced and amateur cybercriminals not only have access to the source code, but a wealth of analysis provided by vendors and cyber security researches like yours truly on how the attacks were executed. I expect we will soon see repurposing and repackaging of the code by numerous copycats.

Additionally, this was one of the first examples of the Equation Group exploits released by the Shadow Brokers being leveraged for a major attack. If WannaCry was perpetrated by a somewhat amateur and inexperienced hacking crew, even with all the mistakes they made, they were still able to launch a global attack that did significant damage. Imagine what more professional cybercriminal gangs and state actors are cooking up right now and potentially preparing to launch in the very near future based not only on these and other exploits, but also lessons learned from the WannaCry proof of concept.

If nothing else, the cybercriminal, hacktivist and cyberterrorist worlds now have a well-documented list of organizations, industry sectors and even countries that are most exposed to similar attacks and an understanding of how much havoc and destruction they could create by pursuing specific cyber-physical and critical system targets.

While the WannaCry attack wasn’t a financial success for its creators, it certainly demonstrated the potential capabilities of the next generation of malware. It’s going to undoubtedly attract both amateur copycats and professionals who are far more skilled and will likely exponentially increase the velocity at which future similar attacks can spread, as well as the ability to inflict and profit from harm.

On the good-guys side, the recent letter from Microsoft calling out the NSA will continue to escalate the growing rift between the technology industry and law enforcement and shine a greater spotlight on the balance between privacy and security for consumers and citizens.

The blame game being played out now between Microsoft and the NSA echoes the debate last year between Apple and the FBI over the creation of “back doors” as well as that regarding the ability for terrorists to use encrypted consumer services such as WhatsApp to communicate and plan attacks.

Once the reports ordered by the President’s Executive Order regarding cybersecurity start coming due in the next 60 and 90 days, we can expect these disputes to continue to escalate as the government and law enforcement rightly seek to define their responsibilities and capabilities to defend the nation and citizens against cyber-attacks. In direct contrast will be vendors’ legitimate needs to provide secure systems and retain customer confidence with regard to privacy and businesses confidentiality.

How Should Companies Prepare?

This is a leadership—not technology—problem. It’s not hard to upgrade your inventory of XP computers to Windows 10 and then keep them patched. That just requires understanding the importance and having the will to do it.

We need to elevate the cybersecurity discussion from the server room to the boardroom. Directors need to understand and approach cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide risk management issue, not just an IT issue, and set the expectation that management will establish an enterprise-wide, cyber-risk management framework with adequate staffing and budget.

Featured Webinars

Hear from our experts on the latest trends and best practices to optimize your network visibility and analysis.

CONTINUE THE DISCUSSION

People are talking about this in the Gigamon Community’s Security group.

Share your thoughts today