WannaCry: Whodunit?

That’s the, er, $61,614.02 question!

The worldwide WannaCry ransomware attack has been making headlines since Friday afternoon when it began running rampant at hospitals in the UK, causing manufacturing plant shut downs across Europe, and propagating and encrypting everything it could get its hands on, from ATMs to marketing display panels.

WannaCry infects unpatched Windows-based computers and immediately encrypts 176 different file types, appending .WCRY to the end of the file name. Once encryption is complete, the user receives a taunting message demanding that a roughly $300 USD bitcoin ransom be paid to decrypt and release the files. If not paid within three days, the demand doubles; if not paid within seven days, WannaCry threatens to delete the files permanently. These tick-tock deadlines are used, of course, to create a sense of urgency for victims to pay.

Uh, Don’t Show Me the Money?

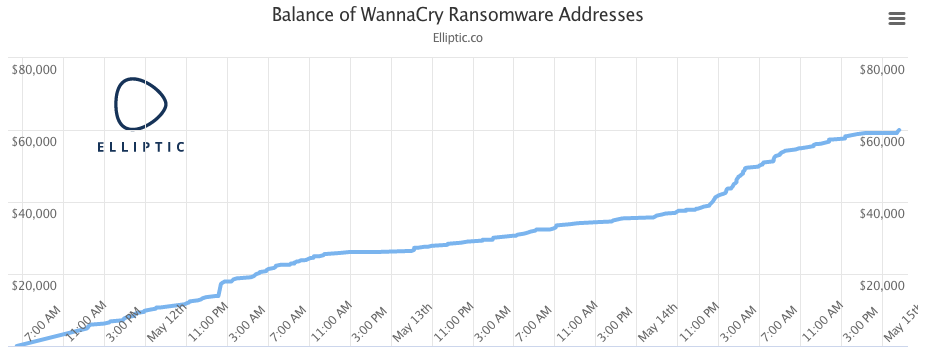

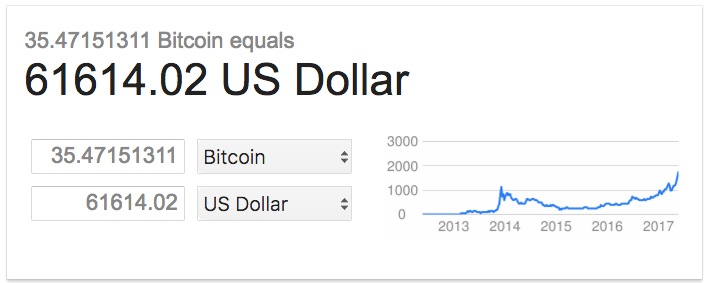

It sounds like a real criminal moneymaker, doesn’t it? With current reports suggesting outbreaks in more than 150 countries and possibly 300,000+ computers infected, at roughly $300 a ransom, you’d think the perpetrators of this global heist would be making off like bandits. But apparently, they’re not.

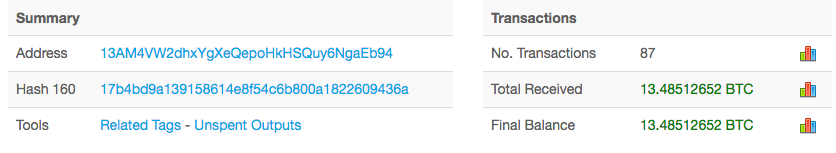

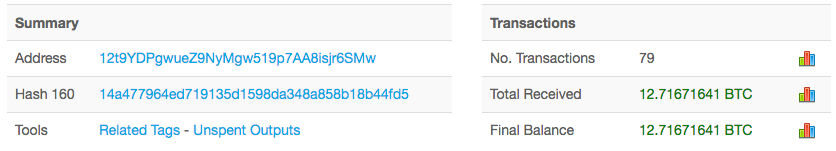

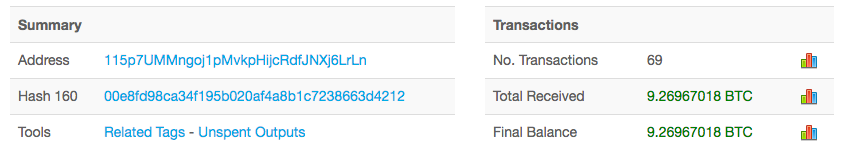

Analysis of the three bitcoin addresses hard-coded into the ransomware indicates that, at the time of writing, a total of 35.47151311 bitcoin ($61,614.02 USD) had been paid in 235 separate transactions.

That’s the great thing about bitcoin. Anyone can view all transactions and check out how many people have actually paid the ransom so far. Have a look for yourself:

Or you just check out this handy, real-time graph prepared by Elliptic:

But Still, Whodunit?

Okay, so we’ve established that whoever did this isn’t getting rich. However, due to the sheer amount of damage done and resulting and continuing chaos from the attack, it’s still important to figure out who is behind it all.

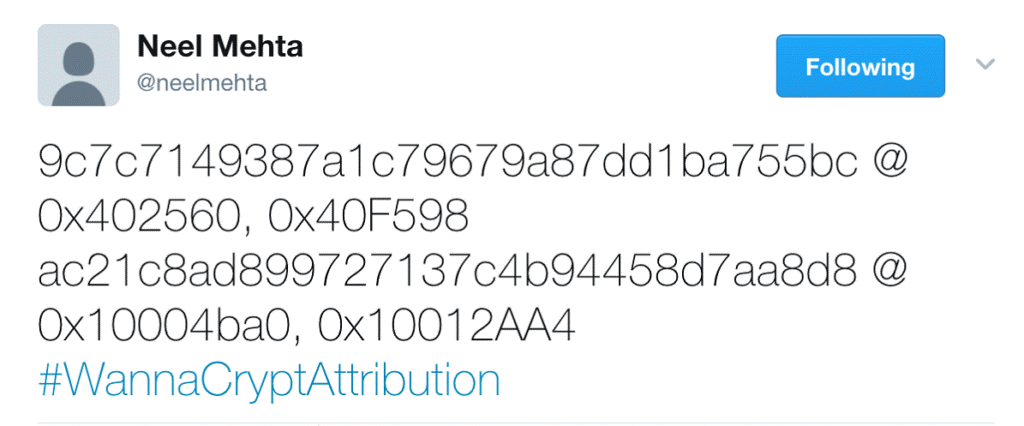

Law enforcement and security researchers have been on the case since Friday and it appears they are making some progress. On Monday, Google Security Researcher Neel Mehta (@neelmehta) posted this tweet along with the hashtag #WannaCryptAttribution.

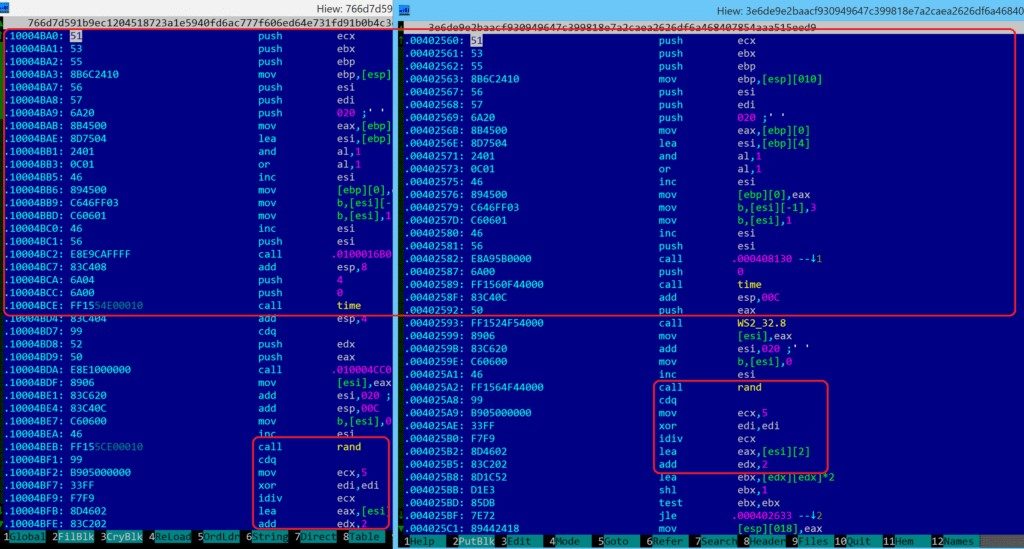

The security research community immediately jumped on the clues he provided and determined that an earlier version of WannaCry, from February 2015, shared some code with a backdoor program known as Contopee. Contopee has been used extensively by a hacker group known as the Lazarus Group. And the Lazarus Group is largely believed to be operating under the control of the North Korean government.

Kaspersky provided the screenshot below that demonstrates the similarity between the two ransomware samples. Shared code has been highlighted.

Source: Securelist, “WannaCry and Lazarus Group—the Missing Link?”

Symantec conducted their own analysis and agrees:

- Co-occurrence of known Lazarus tools and WannaCry ransomware: Symantec identified the presence of tools exclusively used by Lazarus on machines also infected with earlier versions of WannaCry. These earlier variants of WannaCry did not have the ability to spread via SMB. The Lazarus tools could potentially have been used as method of propagating WannaCry, but this is unconfirmed.

- Shared code: As tweeted by Google’s Neel Mehta, there is some shared code between known Lazarus tools and the WannaCry ransomware. Symantec has determined that this shared code is a form of SSL. This SSL implementation uses a specific sequence of 75 ciphers that, to date, have only been seen across Lazarus tools (including Contopee and Brambul) and WannaCry variants.

While these findings do not indicate a definite link between Lazarus and WannaCry, we believe there are sufficient connections to warrant further investigation and will continue to share further details of our research as the case unfolds. (Source: Symantec, “What You Need to Know about WannaCry Ransomware.”)

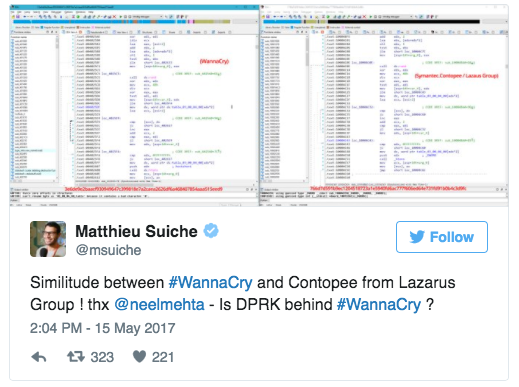

Matt Suiche, who has provided outstanding analysis and commentary on all things WannaCry, has also independently confirmed the similarities in the source code. His full post on attribution is available here.

His full post on attribution is available here.

This isn’t the first time the Lazarus Group has been found to reuse code. BAE Systems earlier linked the hack of Sony Pictures in 2014 with a Bangladesh bank heist of $81 million in 2016, concluding in this report that the malicious code used across the attacks was so similar that both attacks were most likely the work of the same hacking group.

So Did Lazarus or Didn’t Lazarus?

Though too early to say definitively that it was the Lazarus Group and North Korea, it would make a lot of sense. Lazarus Group has a documented history of committing cybercrimes against financial institutions with the primary goal of stealing money, rather than for purposes of espionage or gaining strategic military advantage like other nation state actors. And circumstantial evidence, as mentioned above, is beginning to emerge.

Frankly, with the rather convenient hard-coded kill switch included, the sloppy execution of launching an attack on a Friday afternoon, and the rushed patches to subsequent variants emerging over the past few days, the attack overall just seems to lack the style and sophistication we’ve come to expect from other hacking groups such as Fancy Bear (APT 28).

If attribution to the Lazarus Group is eventually validated, it would be the first nation state-developed ransomware attack that I’m aware of and, likely, the first time that a hostile nation has also leveraged offensive capabilities from the Equation Group release. Whoever did this, they’ve certainly proven themselves to be ingenious and insidious cybercriminals in terms of the development of their attack vector—if rather incompetent at making money. At least, this time.