Considering Threat Hunting

Threat hunting is a popular concept in information security circles, but it’s seldom defined in a rigorous fashion. As a result, many conceptions of “threat hunting” exist, and the idea becomes amorphous, ranging from looking up indicators of compromise (IOCs) to structured, documented programs of iterative searching.

This blog introduces some concepts, explained in greater detail in an accompanying paper, to move our conception of threat hunting into a more formal, intelligence-driven exercise. Doing so allows for improved results and sustainable processes, significantly boosting the security posture of organizations able to implement these steps.

Process

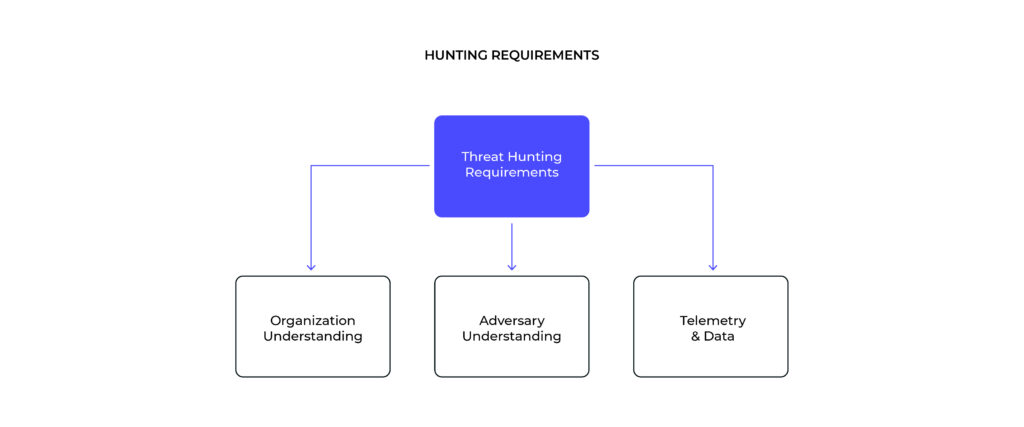

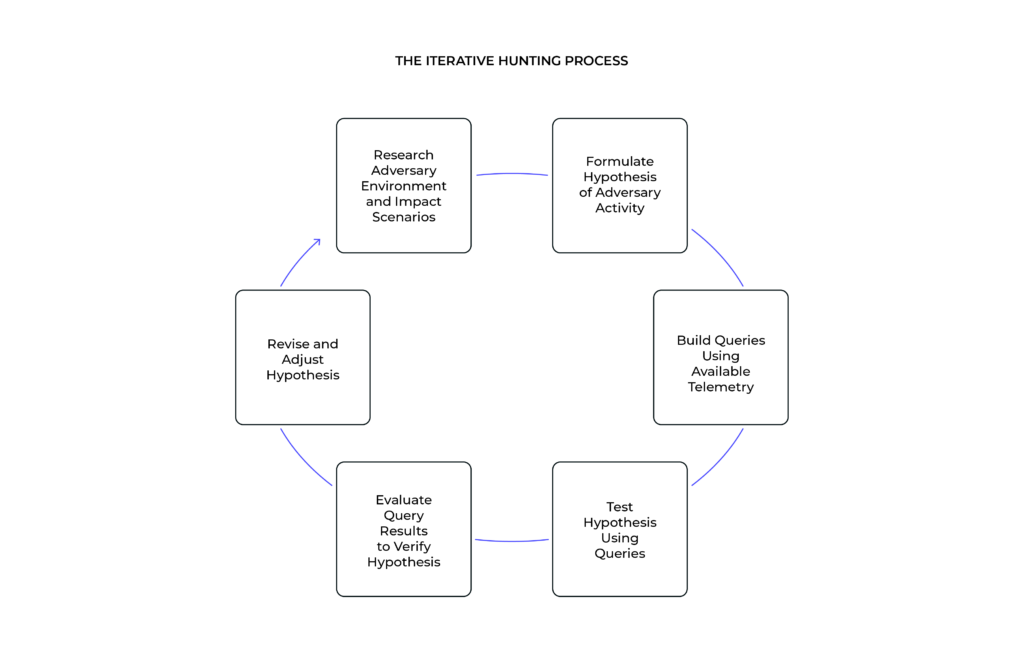

First and foremost, threat hunting is not a single action but a multi-stage process with several key requirements. A proper conception of threat hunting requires moving beyond searching for specific artifacts (for example, searching for IOCs of known past incidents) and instead migrating actions to continuous evaluation of adversary behaviors not otherwise detected or covered by existing security controls.

Threat hunting as a process therefore begins with understanding how adversaries operate. This intelligence-driven effort focuses explicitly on the behaviors, tactics, and techniques employed by threat actors during intrusions. By understanding and unpacking adversary tradecraft, analysts can identify trends and commonalities in adversary actions and begin identifying priority items for further research and investigation.

Understanding the adversary is simply not enough, however. External awareness must be combined with internal understanding of an organization’s capabilities, visibility, and available telemetry. Through this process, analysts can identify the overlap between adversary actions (and the artifacts produced or left behind by them) and defensive visibility. The overlap between these perspectives becomes the area of focus for prospective threat hunting activity and follow-on queries.

Yet the scope of potential hunting activity remains almost overwhelmingly broad given the expanse of the threat landscape. Thus, one final component in structuring threat hunting operations is understanding organization priorities and critical systems.

Organizational analysis can be accomplished through techniques such as “crown jewel” analysis, critical path examination, or related methodology. Irrespective of specific methods used, the goal is to identify what threats are most relevant to the organization and what assets or intrusion routes are most likely to be impacted by adversary operations to focus subsequent threat hunting actions.

Hypothesis Development

With the above prerequisites in place, a prospective threat hunter can begin structuring hypotheses based on a combination of adversary observations, available query mechanisms, and organizational priority. Importantly, all three of these categories must be satisfied to a minimum degree to develop meaningful hypotheses to drive the hunting process.

Once adequate understanding is reached, hypothesis development can proceed. Such statements must be relatively straightforward, simple, and direct while also being open to testing and evaluation within the capabilities of the hunting organization. In cases where the organization formulates a prospective hypothesis that cannot be acted upon, such instances highlight visibility or capability gaps that can be prioritized for future closure.

Testing requires searching for evidence of the hypothesis in available data and evaluating if the unearthed evidence links back adequately to the threat scenario (attacker behavior and organization impact scenario) that informed the original idea.

Evaluation needs to be mindful of how to properly interpret results delivered in the testing phase, differentiating between true and false positives to determine whether results are due to a faulty hypothesis or, instead, a faulty methodology.

Ideally, hypothesis development and follow-on testing take place in an iterative fashion. Results and lessons learned from one round of hunting can and should inform subsequent activities, allowing organizations to both improve specific hunting endeavors while also improving hunting operations more generally.

Detections

Hunting represents a manual intervention to compensate for failures in automated detection. As such, the process is labor-intensive and at times difficult to scale. However, successful hunts can reveal security use cases where detection development is not merely desirable but necessary to address coverage gaps.

Successful hunts — hypotheses where hunters can successfully articulate fruitful searches across internal data sources — can and should be translated into detections when possible. While direct importation of hunting queries to detection rules is likely not feasible, having successfully implemented hunting mechanisms inform subsequent detection engineering is incredibly valuable.

This link between hunting and detections represents an effective mechanism to link long-running alerting with periodic manual intervention to identify and close security gaps. So long as threat hunting informs detection development, and detection engineering alerts hunting operations as to capabilities and coverage, a robust and sustainable security program can emerge.

Conclusion

Threat hunting is a complex and involved topic, requiring the satisfaction of several requirements — adversary understanding, telemetry, and organizational awareness — for successful completion. Organizations that wish to implement a meaningful, sustainable threat hunting program will need to invest in these capabilities and areas of knowledge.

Given requirements, not all organizations will be able to implement a true hunting program without significant investment and improvement in baseline security functions and visibility. For those organizations that have attained the minimal necessary background, though, threat hunting becomes a powerful mechanism to supplement existing alerting and to drive continuous improvement in detection processes.

For additional information, please refer to the Gigamon whitepaper on threat hunting. Additionally, this topic was presented at the 2022 FIRST Conference, recorded here.

Featured Webinars

Hear from our experts on the latest trends and best practices to optimize your network visibility and analysis.

CONTINUE THE DISCUSSION

People are talking about this in the Gigamon Community’s Security group.

Share your thoughts today